by Kelsey Cunningham

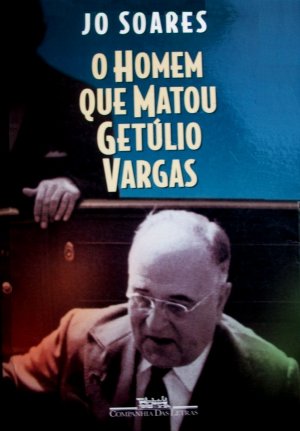

On December 3rd, the Department of Spanish & Portuguese will present a screening of the film Getúlio at the Media Commons Theatre at Robarts Library. On the same theme and also available in the library’s collection of Portuguese language works is the novel O Homen que Matou Getúlio Vargas as well as it’s translation into English, Twelve Fingers: Biography of an anarchist.

Diametrically opposite in every way, the film Getúlio directed by Joao Jardim and the novel O Homem que Matou Getúlio Vargas by Jô Soares recount the fate of the man who governed as dictator from 1930-45 and as democratically elected president from 1951-54. If these works converge on the suicide of the president, the tone and plot could not be any more different between these two works until that fatal end scene at the end of each work.

However, the starkest difference between these works is the point of view from which the story is told. In Getúlio, we see a humanized portrait of the dictator who couldn’t tie his shoes and who loved his daughter Alzira with a moving tenderness. Jardim attempts to plunge the viewer into verisimilitude to the point of choosing actors based on resemblances that seem to bring real historic photographs to life. The book by Soares, however, is told from the perspective of a fictitious would-be assassin. Vargas appears as a minor character who represents a composite of the paradigms which the bumbling twelve-fingered Dimo endeavours to tear down.

Despite the fact that his political career spanned decades, Jardim’s film intimately zeros in on the chaos of the presidential palace and the psychology of the president during his final days. The Man who Killed Getúlio Vargas, on the other hand, spans the entire life of protagonist Dmitri Borja and his journeys as frustrated political assassin across the globe from his failed attempt targeting Franz Ferdinand to 24 August 1954.

The dramatic tone of the film highlights President Vargas’ resolve to not let the media-fueled coup d’état take him down alive. The film emphasizes the dictator’s innocence within the eye of a storm of his government’s endemic corruption; regarding the murders committed by his personal guard, Vargas affirms “not to have committed any crime”. The film goes to the verge of martyrizing the president through the inclusion of actual footage of widespread mourning as his coffin is ceremoniously paraded through the streets of Rio. Indeed, the president’s suicide is portrayed as a sacrifice for the people.

The humorous and light-hearted tone of Soares’ work lends itself to the feel of a quasi-picaresque novel whose cast of characters are pulled from the underworld of anarchy, gangs, and brothels. The work also includes caricatured versions of international literary and historical personalities, weaving the episode of Vargas’ suicide into the tapestry of western popular culture.

If Jardim’s film verges on the sanctification of Vargas’ suicide as a patriotic and desperate act, Soares’ novel is the profanation of Death and the political ideologies that call for it.