by Lucas Lee

In 1993, a hip-hop band called The Coup released their first studio album. Titled Kill My Landlord, the album made waves with its explicitly politically-charged lyrics, most of which written by frontman of the band, Boots Riley. Riley addressed topics from police violence to British involvement in the Opium Wars, each time adopting an outlook that would be considered far-left today, let alone in the George H. W. Bush-era 90s. Riley intended for Kill My Landlord to be an artistic work that inspires revolution. This intent is expressed literally in “The Coup”, the fourth song on the album. The facets of society against which Riley intends to lead a revolution are also explicitly expressed in the lyrics of the album–time and again, Riley condemns two things: institutionalized racism and capitalism. Both themes of racism and capitalism are at the forefront of Riley’s directorial and screenwriting debut, Sorry to Bother You. In this essay, it will be argued that Riley, in Sorry to Bother You, uses subtle directorial techniques in his mise-en-scène, namely his use of colours, to make his statement on racism, while using anomalous devices in the plot and dialogue to represent his more radical views on capitalism.

Institutionalized racism and unethical capitalists

Sorry to Bother You tells the story of Cassius Green, played by Lakeith Stanfield. He is a young, black man in his 20s, hailing from Oakland, California. Due to his unemployment, he is four months behind on his rent, and feels shame that he is unable to provide for himself and his girlfriend, Detroit. Desperate for any job, Cassius lands as a position as a telemarketer at a call centre. He becomes extremely successful at his job shortly after he discovers his talent at channeling his “white voice”. By impersonating an exaggerated stereotype of a Caucasian male, Cassius quickly moves up the ranks of his company, WorryFree, eventually joining the elites. At the same time, his co-workers, who are still stuck in the lowest level of WorryFree, organize a walkout, protesting the company’s underpayment of workers and its questionable ethics. Cassius’s rise in social class alienates him from his friends and girlfriend, who seek to take down the very company that is providing for him.

Sorry to Bother You is hardly the first film to address both institutionalized racism against African-Americans and the unethical behaviours of upper-class capitalists. Peter Farrelly’s Best Picture-winning Green Book (2018) tells the story of Don Shirley, a revered pianist that is ostracized by the mostly white audience for whom he performs. Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989) depicts the lives of young black and Hispanic adults struggling to survive and make money in a neighbourhood devoid of opportunity for social mobility. In terms of portraying racism and the adverse effects of capitalism, the difference between Sorry to Bother You and Green Book or Do the Right Thing is found in Riley’s careful combination of common tropes found in political films and eccentric unorthodox directorial decisions that are jarring to the point being off-putting. In that way, Sorry to Bother You reflects the radicality of Riley’s views from a moderate liberal’s perspective. Most liberals would agree with Riley that there have been institutional barriers to racial equality (Gillborn 8). On the other hand, Riley’s staunch anti-capitalism sentiments would be considered radical to almost all, as most left-leaners seek solutions to inequality within the post-industrial socioeconomic climate rather than without (Muller 49).

Politically-Charged Colours

The film opens with a close-up shot of Stanfield. Stanfield’s eyes dart around the room sheepishly. He is dressed in a dark-coloured business casual outfit and of a dark complexion, juxtaposed with the bright yellow room behind him. The next shot is a medium-wide shot that reveals that Cassius Green is in a side office of a telemarketing sales floor. The colours used in this shot are the first politically-charged statement Boots Riley makes. The interior of the side office features only warm colours outside of Cassius. The walls are yellow, the room is lit by a soft yellow lamp light, and the middle-aged Caucasian manager is dressed in a white shirt. In the same shot, Riley presents the telemarketing sales floor: a large room with rows of small cubicles. The sales floor is completely blue – the walls, the equipment, and the clothes of the minimum-wage-earning telemarketers, none of whom happen to be white. With just the second shot of the film, Riley sets up the economic and racial context of the setting of the film: the white people in this film live in warmth and comfort, represented by yellow, and later, red. The people of colour in this film live in cold and desolate, represented by blue, brown, and later black.

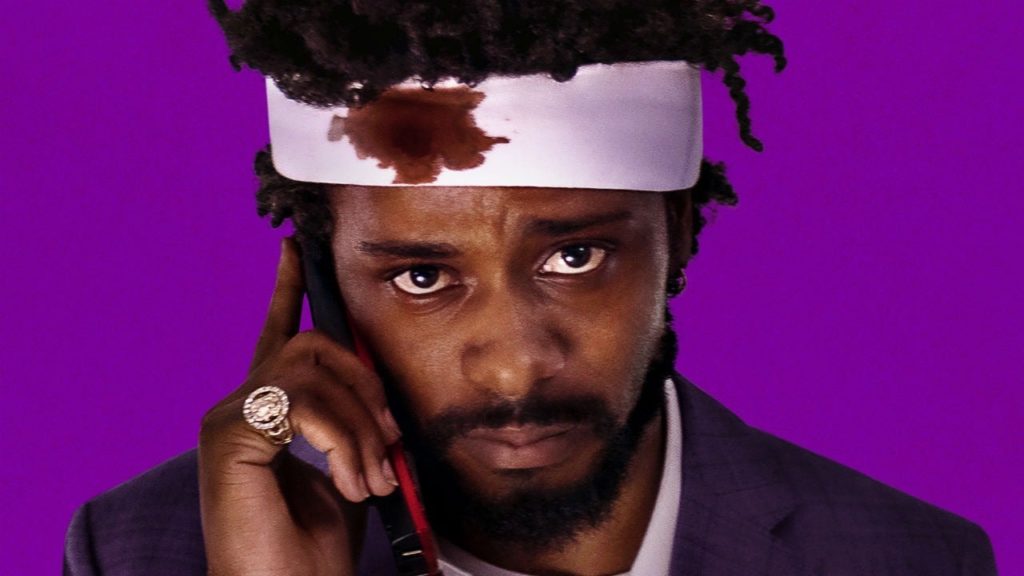

According to Valdez and Mehrabian, short-wavelength colours, such as blue or purple, invoke fewer feelings of desire and arousal than long-wavelength colours, such as yellow or red (396). For that reason, the locations which non-white people occupy throughout the film are constantly given a blue hue. The call centre, the street on which Cassius’s friends protest, and the run-down bar he frequents are all examples of blue settings. In contrast, the elevator that leads to the offices of elite white people is strikingly gold and deep red in colour. The white billionaire who serves as the antagonist of the film lives in a house of soft yellows and dark oranges. The places Cassius desires to be are all yellow, orange, or red, whereas the places he wishes to leave behind are blue and purple. He even switches from wearing exclusively blue shirts and ties to dressing in a gray suit accented by a red tie and the bright red blood that gushes from his forehead halfway through the films. The only character of colour that sports a “desirable colour” is Cassius’s girlfriend Detroit, with her bright orange hair. Riley’s use of colour is a subtle declaration of his views on racial inequality – non-white characters are excluded from the red, orange, and gold world in which the wealthy live.

The White Voice of Capitalism

The most on-the-noise representation of Riley’s views on race relations is the “white voice” motif. Cassius is unsuccessful in almost every definition of the word. He is seldom employed and four months behind on his rent. It is implied that there is no support available to Cassius by his parents, as his uncle is revealed to be the only parental figure in his life. At his telemarketing job, he struggles to make a single sale. It is only until after he learns how to speak in his “white voice” that his social and financial status change. Cassius, when speaking in that tone of voice, is voiced by actor David Cross, although acted (and mouthed) by Stanfield. Stanfield’s mouthing of Cross’s lines is intentionally unsynchronized, leaving the viewer jarred to the point of being taken out of the viewing experience. Sorry to Bother You makes the point that so long as Cassius continues to speak in his natural “black” tone, the general public will reject him, completely inhibiting him from success. It is only when Cassius is played by David Cross, a white man, as opposed to Lakeith Stanfield, that the character is able to escape lower class life.

Whereas Riley’s criticism of the treatment of black people and black culture comes in the form of directorial decisions, his criticism of capitalism is deeply embedded into the plot. The system of capitalism is represented by a fictional company called WorryFree, as the only corporation even tangentially related to the plot. WorryFree’s business model is the following: ordinary citizens sign up to live in WorryFree’s facilities, where housing and food is complimentary, in exchange for factory labour. The characters in the film, Cassius, Detroit, and their friends, are well aware of the similarities between WorryFree and slave owners. These characters go as far as to use the word “slavery” to describe WorryFree’s business model. Not only that, but it is later revealed in the film that WorryFree is actually developing a serum that turns its factory workers into hybrid horse-people – bipedal horses with human arms, much more physically capable than humans, and therefore more profitable in the workplace.

Slavery Work: Dark Humor and Horse-People

The premise is unapologetically silly and absurd. With the shocking reveal of the horse-people, the film goes from a lighthearted drama with comedic undertones to an atypical horror. The colours of the film become darker, and the soundtrack becomes markedly different. The non-diegetic music transitions from synthesizer-based tracks to melodies led by the string section of an orchestra. The strings repeatedly play a pulsing melody in a minor key, which is typical of the instrumental background of traditional horror films (Evans 112-115). In other words, when the true intentions of WorryFree, and therefore capitalism are revealed, the film abruptly switches genres, employing a completely different type of soundtrack along with darker colours and several jump scares.

Means of production are used as a plot device earlier in the film, when Squeeze, one of Cassius’s co-workers, organizes a protest on behalf of the lowly telemarketers. Squeeze asserts that the gains from the efforts of labour should be distributed amongst labourers, as opposed to injected directly into a corporation’s capital. It is at this point in the film that Riley lets it be known that he operates under a Marxian school of thought. Just as in Marx’s system, Squeeze “seizes the means of production” by way of forming a union (Milios and Dimoulis 52). Just like Riley, Squeeze, Detroit, and later Cassius, are all staunch supporters of workers’ rights, and therefore orthodox Marxism. While the film is explicit in comparing the exploitation of labour to slavery, Riley attempts to dilute his support of a communism by representing the system with the widely praised institution of a labour union. Still, even today, when the general political landscape is as progressive as ever, and thereby accepting of new ideas, an unabashed rejection of capitalism difficult to digest – almost as difficult to digest as a crude horse-human hybrid creature that speaks in perfect parlance.

Conclusion

Sorry to Bother You is a marriage

between traditional and radical. With the injection of sci-fi elements, i.e.,

the horse-human hybrids, Boots Riley is blatantly making the comparison between

labourers and animals. Riley employs common directing techniques that have been

used since the dawn of cinema. Riley transitions from a radical leftist hip-hop

artist to an equally radical filmmaker. In Kill

My Landlord, Riley states his intention to lead revolution against the

government and the extremely wealthy. He expresses a deep dissatisfaction with

the discrimination of black Americans by the government, its institutions such

as police and education systems, and the upper classes. Riley does the same in Sorry to Bother You, but constrained to

the medium of film, he uses traditional techniques to manipulate the viewer’s subconscious. At the same time,

Riley is unable to restrain his fixation for unambiguity. This essay proves

that the end result of Riley’s explicit style of music crossed with the medium

of cinema is a film that uses subtle changes in colour, music, and genre to

express one of its thesis: that the inequality between white and non-white

people is propagated by the inherently unequal system of capitalism. Also, the

film uses unambiguous plot devices to present its other thesis: capitalism

breeds corporations that do not distinguish between labourers and slaves.

Works Cited

Evans, Mark. “Rhythms of evil: exorcizing sound from the exorcist”. In Hayward, Philip. Terror tracks: music, sound and horror cinema. London: Equinox Publishing, 2009, p.112-124.

Gillborn, David. “Critical race theory and education: Racism and anti-racism in educational theory and praxis.” Discourse: Studies in the cultural politics of education 27.1 (2006): 11-32.

Milios, John, and Dimitri Dimoulis. Karl Marx and the classics: An essay on value, crises and the capitalist mode of production. Routledge, 2018.

Muller, Jerry Z. “Capitalism and inequality: What the right and the left get wrong.” Foreign Aff. 92 (2013): 30.